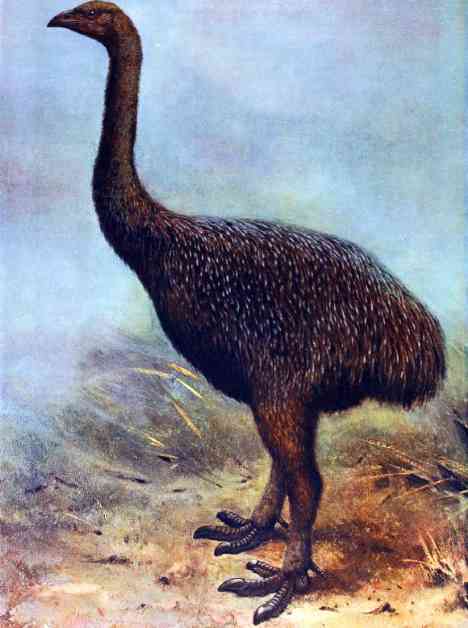

Human settlement on islands in the Pacific Ocean led to the extinction of many animals, including the moa, a large, wingless bird native to New Zealand. A recent study by scientists from the University of Adelaide and other institutions examined the range and extinction patterns of six moa species in New Zealand. They discovered that the last populations of moa survived in cold, mountainous regions that were less affected by human activity.

Dr. Damien Fordham, a researcher at the University of Adelaide, explained that their research used advanced models and fossil records to track the population dynamics of moa species. Despite differences in ecology and extinction timing, all moa species eventually disappeared from similar areas on New Zealand’s North and South Islands. These areas, such as Mount Aspiring and the Ruahine Range, are now sanctuaries for New Zealand’s remaining flightless birds.

Dr. Sean Tomlinson, another researcher from the University of Adelaide, suggested that moa likely vanished first from lowland habitats preferred by Polynesian settlers. As human impact increased, moa populations declined, with the last individuals seeking refuge in remote, mountainous environments. Interestingly, these ancient refugia now support populations of modern flightless birds like takahē, weka, and great spotted kiwi.

The study also highlighted the overlap between the last moa populations and critically endangered species like the kākāpō. Dr. Jamie Wood, also from the University of Adelaide, emphasized that these refugia were not necessarily ideal habitats for flightless birds, but rather areas least affected by human activity. Similar to past colonization patterns, European settlement in New Zealand led to habitat destruction that forced flightless birds into isolated, mountainous regions.

The findings of the research team were published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, shedding light on the importance of preserving these refugia for the conservation of New Zealand’s unique bird species. The study’s insights into the extinction dynamics of moa provide valuable information for ongoing efforts to protect the country’s remaining flightless birds and their habitats.